News & Events

How Antibodies and Antigens Drive Transplant Rejection

When you look at transplantation of organs, you must distinguish between an antibody and an antigen to understand why transplant rejection happens. Antigens are unique markers on donor cells. Antibodies, made by your immune system, target these antigens. If you cannot distinguish between an antibody and an antigen, you may not see how immunity reacts to foreign tissues. In immunology, doctors use tests to distinguish between an antibody and an antigen. This helps them predict rejection. Immunology research shows that recognizing alloantibodies and antibody responses to transplantation improves outcomes. If you distinguish between an antibody and an antigen, you help protect grafts. Immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity, immunity. Alloantibodies, alloantibodies, alloantibodies.

Key Takeaways

- Understand the difference between antibodies and antigens. Antigens are markers on donor cells, while antibodies are proteins your immune system makes to target those markers.

- Matching human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) between donor and recipient is crucial. This reduces the risk of transplant rejection and improves graft survival.

- Regular monitoring for donor-specific antibodies is essential. Early detection can help manage risks and improve outcomes for transplant patients.

- Immunosuppressive medications can help prevent rejection. Following your treatment plan and attending check-ups are vital for maintaining a healthy graft.

- Recognize the types of transplant rejection: hyperacute, acute, and chronic. Each type has different mechanisms and timelines, affecting how doctors manage your care.

Distinguish Between an Antibody and an Antigen

What Is an Antigen?

You need to know what an antigen is to understand transplant rejection. An antigen is a marker found on the surface of cells. In transplantation, antigens from donor tissue act as signals to your immune system. Your body checks these markers to decide if a cell belongs or if it is foreign. When you receive an organ, your immune system looks for antigens that do not match your own. If it finds unfamiliar antigens, it may attack the new tissue.

- Human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) help your immune system tell the difference between your own cells and foreign cells.

- When donor tissue has different HLAs, your immune system may see these antigens as threats.

- This reaction can lead to organ rejection.

- Doctors use tissue typing to match HLAs between donor and recipient. This lowers the chance of rejection.

“The two major types of antigens expressed in donor organs are called MHC class I and MHC class II.”

You will see that antigens play a central role in how your body reacts to a transplant. The immune system targets these antigens, which can lead to rejection if they are not matched well.

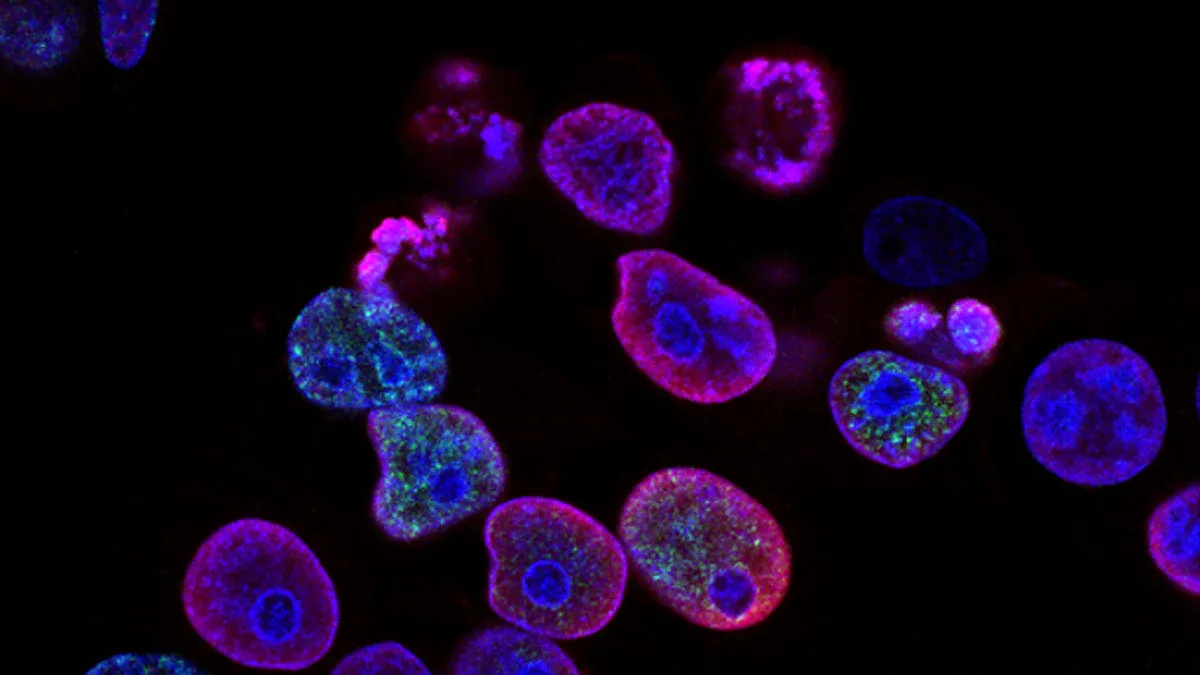

What Is an Antibody?

An antibody is a protein made by your immune system. B cells, a type of white blood cell, produce antibodies. These proteins find and attach to antigens that do not belong in your body. When you get a transplant, your B cells may see donor antigens as foreign. They then make antibodies that target these antigens.

- B cells need help from T cells to make antibodies against donor antigens.

- T cells recognize antigens presented on MHC class II molecules.

- B cells can take in foreign proteins, show them to T cells, and get help to activate.

- Over time, B cells improve their ability to recognize the antigen.

- Some B cells become memory cells and can quickly make antibodies if they see the antigen again.

You must distinguish between an antigen and an antibody. The antigen is the marker that triggers the response. The antibody is the protein that targets the antigen. If you understand this difference, you can see why matching antigens is so important in transplantation. It helps prevent your immune system from making antibodies that attack the new organ.

Antibodies in Transplantation

Donor-Specific Antibodies

When you receive a transplant, your immune system can make antibodies that target the donor organ. These are called donor-specific antibodies. They recognize the unique antigens on the donor tissue and can trigger rejection. You may hear doctors talk about anti-donor antibodies or anti-HLA antibodies. These antibodies in transplantation play a major role in how your body reacts to the new organ.

You can see how common donor-specific antibodies are in transplant patients:

- In a study of lung transplant recipients, 13.2% had donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies.

- Other studies show rates of 14%, 20%, and 32% in different groups.

- In heart transplantation, 9.4% of patients had donor-specific antibodies before surgery.

Donor-specific antibodies can appear before or after transplantation. If you have these antibodies before the transplant, you face a higher risk of graft rejection. After transplantation, your immune system can develop new anti-donor antibodies. These antibodies against a graft can attack the new tissue and cause problems.

Doctors watch for donor-specific antibodies because they can predict how well your graft will work. In kidney transplantation, the presence of donor-specific antibodies links to worse outcomes. Pretransplant donor-specific antibodies can lead to acute rejection. You need careful monitoring if you have these antibodies. Sometimes, even with donor-specific antibodies, about half of patients can still keep good graft function for a long time. The relationship between donor-specific antibodies and T-cell–mediated rejection is complex and not fully understood.

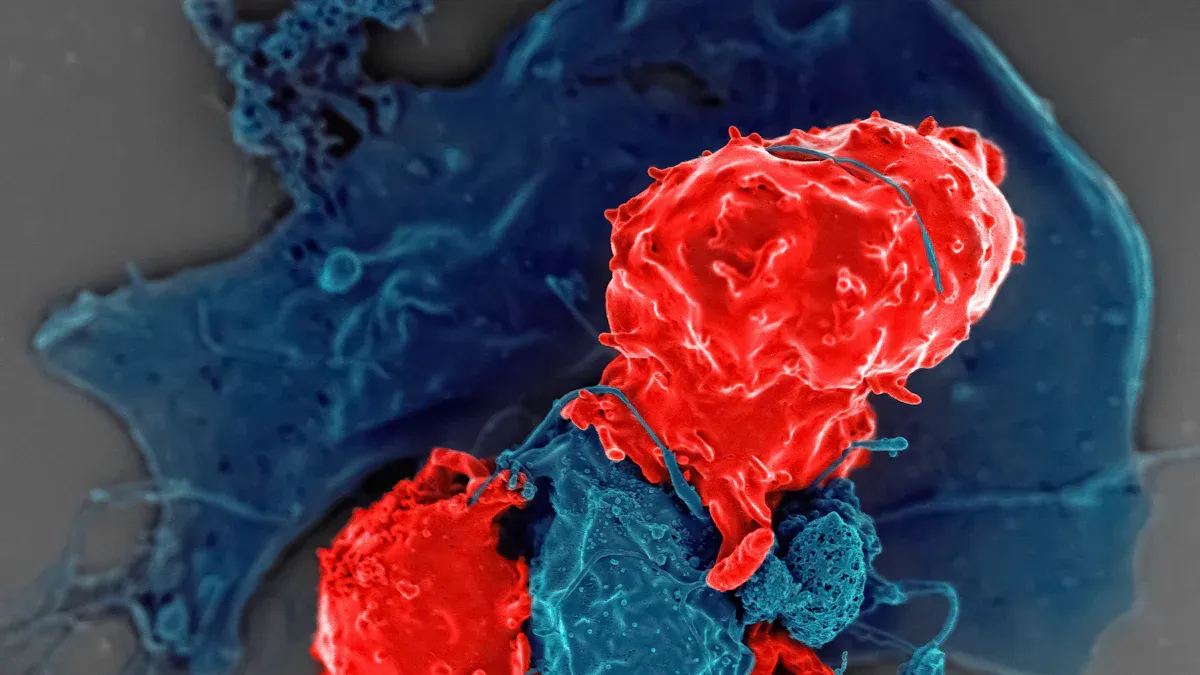

Antibody-Mediated Rejection

Antibody-mediated rejection happens when your immune system uses antibodies to attack the transplanted organ. This process is different from cellular rejection, which uses immune cells. Antibody-mediated injury can damage the blood vessels in the graft. When anti-donor antibodies bind to the antigens on the graft, they can start a chain reaction that leads to tissue injury and cell death.

You can see how antibodies cause vascular injury and graft loss in transplantation in the table below:

| Evidence Description | Details |

|---|---|

| Presence of donor-specific antibodies as a biomarker | Donor-specific antibodies predict poor transplant outcomes, including high rates of antibody-mediated rejection and graft dysfunction. |

| Risk factors for donor-specific antibody development | High HLA mismatches, not enough immunosuppression, and graft inflammation raise the risk. |

| Mechanism of graft injury | Donor-specific antibodies can activate the complement pathway and cause antibody-mediated injury through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. This leads to tissue injury and cell death. |

| Endothelial cell activation | Donor-specific antibodies can make endothelial cells grow and produce more vascular endothelial growth factor, which adds to graft injury. |

When you have anti-donor antibodies, you face a higher risk of antibody-mediated rejection. This type of rejection can happen early or late after transplantation. Doctors call this process humoral rejection because it involves antibodies in the blood, not just immune cells.

The humoral theory of rejection says that antibodies, not just cells, drive graft rejection. Clinical studies show that patients with antibodies have a failure rate twice as high as those without antibodies. This means antibody-mediated injury is a strong reason for chronic rejection. The presence of HLA antibodies is a strong sign that the graft may not work well. Doctors now focus on managing antibody levels to improve outcomes for patients with grafts.

You need to know that antibody-mediated rejection can look different depending on when it happens. Early antibody-mediated rejection often links to preexisting anti-donor antibodies. Later rejection can come from new antibodies made after transplantation. Doctors use tests to find out if you have anti-donor antibodies and to check for signs of antibody-mediated injury.

You can compare different types of antibody-mediated rejection in the table below:

| Feature | Type 1 ABMR | Type 2 ABMR |

|---|---|---|

| Timing of occurrence | Early post-transplantation | Usually occurs over one year post-transplantation |

| Association with donor-specific antibodies | Persistence or rebound of preexisting antibodies | Associated with new antibodies |

| Interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy | Less frequent | More frequent |

| Frequency of cell-mediated rejection | Less frequent | More frequent |

| C4d positivity | Similar frequencies | Similar frequencies |

| Graft survival | Higher compared to type 2 | Lower compared to type 1 |

You must remember that antibodies in transplantation are not always bad. Sometimes, even with anti-donor antibodies, you can keep your graft working for years. Still, the risk of antibody-mediated injury and antibody-mediated rejection is real. Doctors use tissue typing, immunosuppression, and regular monitoring to lower the risk of graft rejection. By understanding how antibodies against a graft work, you can help protect your new organ and improve your chances for a healthy life with your graft.

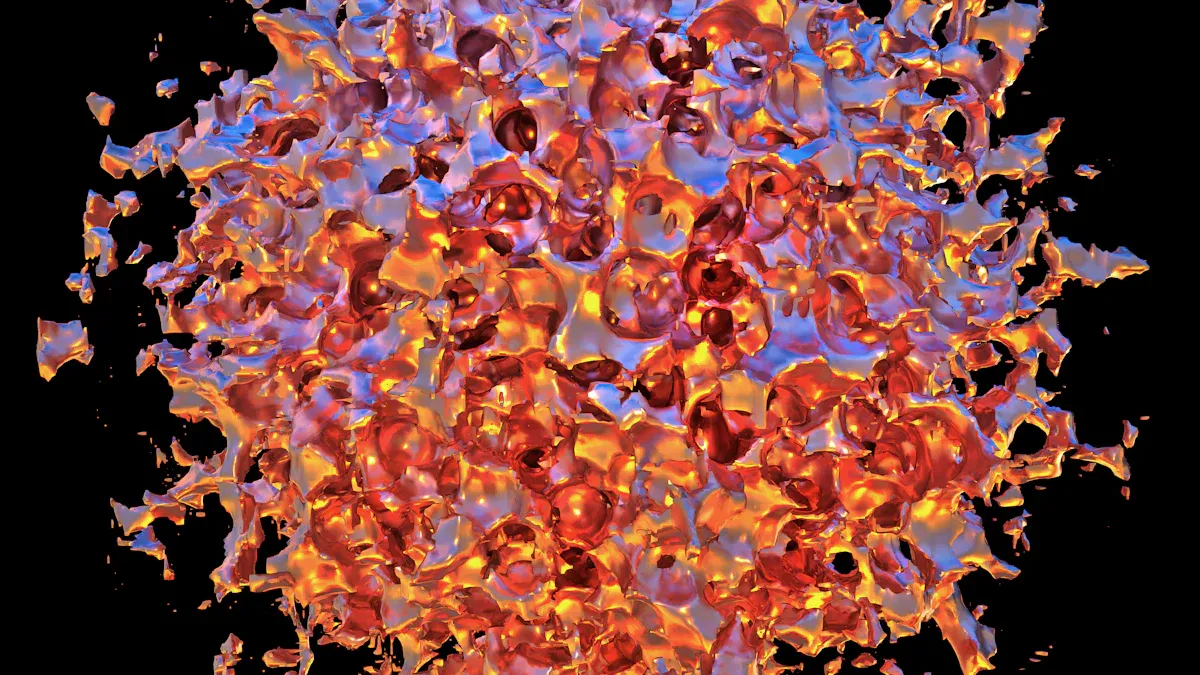

Transplant Rejection Mechanisms

Transplant rejection can happen in different ways. You need to know how your immune system reacts to antigens and antibodies during each type. The three main types are hyperacute, acute, and chronic rejection. Each type involves a unique process and timeline.

| Type of Rejection | Description | Mechanism Involved |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperacute Rejection | Occurs within minutes to hours post-transplant due to pre-existing antibodies against donor antigens. | Rapid activation of the complement system due to antibodies binding to antigens on the donor organ. |

| Acute Rejection | Can occur within days to months after transplantation. | T-cell mediated responses against the transplanted tissue, often manageable with immunosuppressive therapy. |

| Chronic Rejection | Develops over months or years, leading to gradual loss of function in the transplanted organ. | Ongoing immune responses causing fibrosis and blood vessel changes, more complex to manage than acute rejection. |

Hyperacute Rejection

You may see hyperacute rejection right after transplantation. This happens when your body already has antibodies that match the donor’s antigens. These antibodies attack the new organ within minutes or hours. The immune system quickly activates the complement system. Blood flow to the organ stops, and the graft fails. Doctors try to prevent this by checking for pre-existing antibodies before surgery.

Acute Rejection

Acute rejection usually appears days to months after transplantation. Your immune system recognizes foreign antigens on the new organ. T cells attack the tissue, but antibodies can also play a role. You might hear about anti-HLA antibodies and C4d deposits in this process. Doctors use blood and urine tests to find biomarkers like IFN-γ, IP-10, and calprotectin. These help spot acute rejection early. Immunosuppressive drugs can often control this type of rejection.

- B cells and anti-HLA antibodies are important in acute rejection.

- CD20+ B cells and plasma cells in the graft can signal severe rejection.

- Antibody-mediated rejection can cause unique changes in the organ, such as capillary basement membrane thickening.

Chronic Rejection

Chronic rejection develops slowly, sometimes over years. Your immune system keeps reacting to donor antigens. Both T cells and antibodies contribute to this process. The organ’s blood vessels thicken, and scar tissue forms. Over time, the graft loses function. Chronic rejection is hard to treat and often leads to graft loss. About one-third of kidney transplant recipients from deceased donors face this problem within five years. You may also face other health issues if chronic rejection occurs.

- Chronic rejection leads to a poor outlook for the transplanted organ.

- Ongoing immune responses cause lasting damage and health complications.

Understanding how antigens and antibodies drive each type of transplant rejection helps you and your doctors protect your new organ.

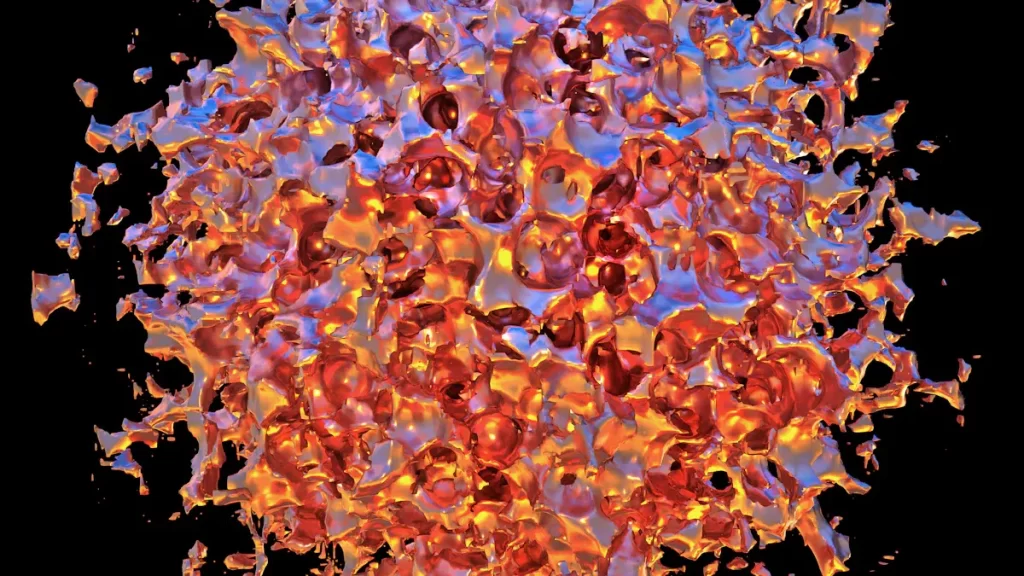

Immune Pathways in Transplantation

When you receive an organ transplant, your body uses two main immune response pathways to decide if the new tissue should stay or be attacked. These are the humoral (antibody-mediated) pathway and the cellular pathway. Both pathways react to foreign antigens, especially those found on the major histocompatibility complex, or MHC. The MHC includes human leukocyte antigen molecules, which act as identity tags for your cells.

Humoral (Antibody-Mediated) Pathway

The humoral pathway centers on antibodies. Your B cells make these proteins when they spot foreign antigens, such as those on donor tissue. In transplantation, antibodies target the donor’s MHC, especially the human leukocyte antigen. This immune response can happen quickly if you already have antibodies from past exposures. When antibodies bind to the donor’s antigens, they can activate the complement system. This leads to damage of the blood vessels in the new organ.

- Antibodies can cause hyperacute rejection within minutes.

- B cells and plasma cells produce donor-specific antibodies that attack the graft.

- The immune response in this pathway often leads to antibody-mediated rejection, which is a major cause of graft failure.

| Immune Response Type | Characteristics | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Humoral Response | Production of antibodies against donor antigens | Mediated by preformed antibodies, often leading to hyperacute rejection |

You may also see that antibodies sometimes protect the graft by blocking other immune attacks. The balance between injury and protection depends on how your immune system reacts to the donor’s MHC.

Cellular Pathway

The cellular pathway relies on T-lymphocytes. These cells recognize donor antigens presented by the major histocompatibility complex. T cells can attack the graft directly or help other immune cells respond. Acute cellular rejection affects more than one-third of lung transplant recipients, showing how important T cells are in this process.

- T cells recognize donor antigens through direct, indirect, or semidirect pathways.

- CD4+ and CD8+ T cells both play roles in the immune response.

- Cellular rejection often develops days to months after transplantation.

| Immune Response Type | Characteristics | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Response | Involves T-lymphocytes | Direct cellular mechanisms leading to acute cellular rejection |

Both pathways start when your immune system detects foreign MHC molecules. The interaction between antibodies, antigens, and T cells drives the immune response. Understanding these pathways helps you and your doctors manage the risk of rejection and improve transplant outcomes.

Clinical Impact of Antibody-Mediated Rejection

Graft Survival and Function

When you receive an organ transplant, your main goal is to keep the new organ working well for as long as possible. Antibody-mediated rejection can make this difficult. If your immune system creates antibodies against the donor organ, these antibodies can attack the tissue and harm its function. Over time, this can lead to a loss of the organ, even if you take your medicine as prescribed.

You can see how antibody-mediated rejection affects graft outcome in the table below:

| Key Findings | Description |

|---|---|

| Impact on Graft Survival | Antibody-mediated rejection significantly challenges long-term graft survival in kidney transplantation. |

| Histopathological Features | Diffuse C4d positivity is linked to poorer graft survival outcomes. |

| Age Dependency | The cumulative incidence of antibody-mediated rejection varies with age, being a major cause of graft loss in younger recipients. |

| Graft Loss Statistics | Over 80% of cases with antibody-mediated rejection will eventually lose their graft. |

| Importance of Early Diagnosis | Early diagnosis is crucial for improving treatment success and graft survival. |

You need to know that early detection and treatment can help improve your graft outcome. Doctors look for signs like high serum creatinine, protein in the urine, and C4d staining to catch problems early.

Risk Factors and Outcomes

Many factors can affect your graft outcome after antibody-mediated rejection. Some of these are related to your immune system, while others depend on your medical history.

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Antibody Specificity | Different antibodies can have varying effects on graft outcome. |

| Isotype/Subclass | IgG2/IgG4 antibodies are linked to stable function, while IgG3/IgG1 are linked to acute rejection. |

| Strength (MFI/Titer) | High levels of donor-specific antibodies increase the risk of hyperacute rejection. |

| Complement Binding | Antibodies that bind complement are associated with acute rejection. |

| Sensitization History | Past events like previous transplants or pregnancies can increase risk. |

Younger age, HLA mismatches, and a history of sensitization all raise your risk for poor graft outcome. If you have pre-formed donor-specific antibodies, you face a higher chance of transplant rejection. Doctors use tissue typing and regular monitoring for donor-specific antibodies to lower these risks. By checking your antibody levels, your care team can spot problems early and adjust your treatment to protect your graft.

Monitoring donor-specific antibodies helps your doctor find hidden injury and treat it before you notice symptoms. This can improve your graft outcome and help your new organ last longer.

Diagnosis and Treatment in Transplantation

Detecting Antibodies and Antigens

You need to know how doctors find antibodies and antigens in your body after transplantation. Doctors use blood tests to look for antibodies that might attack your new organ. These tests include the panel reactive antibody (PRA) test and the Luminex assay. The PRA test shows if you have many antibodies against common antigens. The Luminex assay can find specific antibodies that target donor antigens. Doctors also use tissue typing to match your antigens with those of the donor. This step helps lower the risk of rejection. If your blood has antibodies against donor antigens, your risk of rejection goes up. Regular testing helps your care team catch problems early.

Early detection of antibodies and antigens gives you the best chance to protect your new organ.

Prevention and Management

You can lower your risk of rejection by using two main strategies: tissue typing and immunosuppression. Tissue typing checks the HLA antigens on your cells and matches them with the donor. A close HLA match means your body is less likely to see the new organ as foreign. Immunosuppression uses medicine to calm your immune system. These drugs stop your body from making too many antibodies that could attack the graft.

If you develop antibody-mediated rejection, your doctor may use different treatments. Here is a table that shows some options:

| Treatment Option | Description |

|---|---|

| Antithymocyte Globulin (ATG) | Used for tough cases and mixed rejection; not helpful for pure antibody-mediated rejection; higher infection risk when combined with B-cell depletion. |

| Splenectomy | Surgery for severe early rejection; must be done quickly; patients often become more sensitive after surgery. |

| Bortezomib | Targets plasma cells that make antibodies; works best with other treatments; not enough data for use alone. |

| Cyclophosphamide | Used in some tough cases; only anecdotal support for its use in antibody-mediated rejection. |

| Interleukin-6 Inhibitors | Tocilizumab may help patient and graft survival; more studies are underway for other drugs like Clazakizumab. |

You should follow your treatment plan and attend regular check-ups. Your care team will monitor your antibodies and antigens to keep your new organ healthy.

You now know that antigens act as markers on donor cells, while antibodies are proteins your body makes to target these markers. This difference is key in transplant rejection. When you understand these roles, you help doctors choose better matches and spot problems early.

| Mechanism/Technique | Description | Impact on Transplant Rejection |

|---|---|---|

| Donor-Specific Antibodies (DSA) | Identified through Luminex assay | Independent predictor of allograft loss; reduction in DSA correlates with higher graft survival |

| HLA Typing | Identifies unacceptable antigens | Helps avoid rejection by selecting compatible donors |

| Flow Crossmatching | Determines T- or B-cell compatibility | More accurate prediction of rejection, especially with positive T-cell crossmatch |

Recent studies show that teamwork among doctors, immunologists, and pathologists leads to better care for transplant patients. You can support ongoing research and awareness to help more people enjoy healthy transplants in the future.

FAQ

What is the difference between an antibody and an antigen?

Antigens are markers on donor cells. Antibodies are proteins your immune system makes to target those markers. You need to know this difference to understand transplant rejection.

How do doctors check for donor-specific antibodies?

Doctors use blood tests like the Luminex assay. This test finds antibodies that match donor antigens. You may hear your doctor talk about your panel reactive antibody (PRA) score.

Can you prevent transplant rejection?

You can lower your risk by matching donor and recipient antigens. Doctors use tissue typing and immunosuppressive drugs. Regular monitoring helps catch problems early.

What are signs of antibody-mediated rejection?

You may see high creatinine levels, protein in your urine, or swelling. Doctors look for C4d staining in tissue samples. Early diagnosis improves your chances for a healthy graft.

Why do some people develop donor-specific antibodies after transplant?

Your immune system may react to new antigens in the donor organ. Past transplants, blood transfusions, or pregnancies can increase your risk. Doctors monitor you for these antibodies to protect your graft.